In-Depth Quantum Mechanics

This page is print-friendly. Simply press Ctrl + P (or Command + P if you use a Mac) to print the page and download it as a PDF. Report an issue or error here.

Table of contents

Note: it is highly recommended to navigate by clicking links in the table of contents! It means you can use the back button in your browser to go back to any section you were reading, so you can jump back and forth between sections!

- Prerequisites

- Foreword

- Basics of wave mechanics

- Exact solutions of the Schrödinger equation

- The state-vector and its representations

- Quantum operators

- Observables

- The density operator and density matrix

- Introduction to intrinsic spins

- The quantum harmonic oscillator

- Time evolution in quantum systems

- Angular momentum

- Stationary perturbation theory

- Advanced quantum theory

This is a guide to quantum mechanics beyond the basics, and is a follow-up to introductory quantum physics. Topics convered include state-vectors, Hilbert spaces, intrinsic spin and the Pauli matrices, the hydrogen atom in detail, the quantum harmonic oscillator, time-independent perturbation theory, and a basic overview of second quantization and relativistic quantum mechanics.

I thank Professor Meng and Professor Shi at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, without whom this guide would not have been possible.

Prerequisites

This guide will assume considerable prior knowledge, including multivariable & vector calculus, linear algebra, basic quantum mechanics, integration with delta functions, classical waves, Fourier series, solving boundary-value problems, and (in later chapters) tensors and special relativity. If you don't know some (or all) of these, that's okay! There are dedicated guides about each of these topics on this site:

- For a review of calculus (in particular multivariable and vector calculus), see the calculus series

- For a review of the classical theory of waves, see the waves and oscillations guide

- For a review of basic quantum mechanics, see the introductory quantum mechanics guide

- For a review of electromagnetic theory, see the fundamentals of electromagnetism guide as well as the in-depth electromagnetism guide

- For a review of boundary-value problems, Fourier series, and see the PDEs guide

- For a review of special relativity and tensors, see the advanced classical mechanics guide

Foreword

Quantum mechanics is a fascinating subject. Developed primarily in the early 20th-century, it is a theory that (at the time of writing) is barely a hundred years old, but its impact on physics and technology is immense. Without quantum mechanics, we would not have solid-state hard drives, phones, LED lights, or MRI scanners. Quantum mechanics has revolutionized the world we live in, and this is despite the fact that it governs the behavior of particles smaller than we could ever possibly see. But understanding how matter behaves at tiny, microscopic scales is the key to understanding how matter on macroscopic scales behaves. Quantum mechanics unlocks the secrets of the microscopic world, and however unintuitive it may be, it is the best (nonrelativistic) theory we have to understand this strange, mysterious world.

Basics of wave mechanics

In classical physics, it was well-known that there was a clear distinction between two phenomena: particles and waves. Waves are oscillations in some medium and are not localized in space; particles, by contrast, are able to move freely and are localized. We observe, however, in the quantum world, that "waves" and "particles" are both incomplete descriptions of matter at its most fundamental level. Quantum mechanics (at least without the inclusion of quantum field theory) does not answer why this is the case, but it offers a powerful theoretical framework to describe the wave nature of matter, called wave mechanics. In turn, understanding the wave nature of matter allows us to make powerful predictions about how matter behaves at a fundamental level, and is the foundation of modern physics.

Introduction to wave mechanics

From the classical theory of waves and classical dynamics, we can build up some basic (though not entirely correct) intuition for quantum theory. Consider a hydrogen atom, composed of a positively-charged nucleus, and a negatively-charged electron. Let us assume that the nucleus is so heavy compared to the electron that it may be considered essentially a classical point charge. Let us also assume that the electron orbits the nucleus at some known distance $R$. For the electron to not decay and fall into the nucleus, classical mechanics tells us that its potential energy and kinetic energy must balance each other. Thus, the electron must both be moving and have some amount of potential energy, which comes from the electrostatic attraction of the electron to the nucleus. This bears great resemblance to another system: the orbital motion of the planets around the solar system.

However, experiments conducted in the early 20th century revealed that atoms emit light of specific wavelengths, meaning that they could only carry discrete energies, and therefore only be found at certain locations from the nucleus. This would not be strange in and of itself, but these experiments also found that electrons could "jump" seemingly randomly between different orbits around the nucleus. That is to say, an electron might initially be at radius $R_1$, but then it suddenly jumps to $R_3$, then jumps to $R_2$, but cannot be found anywhere between $R_1$ and $R_2$ or between $R_2$ and $R_3$. This meant that electrons could not be modelled in the same way as planets orbiting the Sun - this jumpy "orbit" would be a very strange one indeed!

Instead, physicists wondered if it would make more sense to model electrons as waves. This may seem absolutely preposterous on first inspection, but it makes more sense when you think about it more deeply. First, a wave isn't localized in space; instead, it fills all space, so if the electron was indeed a wave, it would be possible to find the electron at different points in space ($R_1, R_2, R_3$) throughout time. In addition, waves also oscillate through space and time at very particular frequencies. It is common to package the spatial frequency of a wave via a wavevector $\mathbf{k} = \langle k_x, k_y, k_z\rangle$ and the temporal frequency of a wave via an angular frequency $\omega$ (for reasons we'll soon see). Since these spatial and temporal frequencies can only take particular values, the shape of the wave is also restricted to particular functions, meaning the pulses of the wave could only be found at particular locations. If we guess the pulses of the wave to be somehow linked to the position of the electron (and this is a correct guess!), that would neatly give an explanation for why electrons could only be found at particular orbits around the nucleus and never between two orbits.

The simplest types of waves are plane waves, which may be described by complex-valued exponentials $e^{i(\mathbf{k} \cdot \mathbf{x} + \omega t)}$, or by equivalent real-valued sinusoids $\cos(\mathbf{k}\cdot \mathbf{x} + \omega t)$. Thus, it would make sense to describe such waves with a complex-valued wave equation, where we use complex numbers for mathematical convenience (it is much easier to take derivatives of complex exponentials than real sinusoids). To start, let's assume that our electron is a wave whose spatial and time evolution are described by a certain function, which we'll call a wavefunction and denote $\Psi(x, t)$. We'll also assume for a free electron far away from any atom, the wavefunction has the mathematical form of a plane wave:

$$ \Psi(x,t) = e^{i(\mathbf{k} \cdot \mathbf{x} - \omega t)} $$

Note that if we differentiate our plane-wave with respect to time, we find that:

$$ \dfrac{\partial \Psi}{\partial t} = \dfrac{\partial}{\partial t}e^{i(\mathbf{k} \cdot \mathbf{x} - \omega t)} = \dfrac{\partial}{\partial t} e^{i\mathbf{k} \cdot \mathbf{x}} e^{-i\omega t} = -i\omega e^{i(\mathbf{k} \cdot \mathbf{x} - \omega t)} = -i\omega \Psi(x, t) $$

We'll now introduce a historical discovery in physics that transforms this interesting but not very useful result into a powerful lead for quantum mechanics. In 1905, building on the work by German physicist Max Planck, Albert Einstein found that atoms emit and absorb energy in the form of light with a fixed amount of energy. This energy is given by the equation $E = h\nu$ (the Planck-Einstein relation), where $h = \pu{6.62607015E-34 J*s}$ is known as the Planck constant, and $\nu$ is the frequency of the light wave. Modern physicists usually like to write the Planck-Einstein relation in the equivalent form $E = \hbar \omega$, where $\omega = 2\pi \nu$. Armed with this information, we find that we can slightly rearrange our previous result to obtain an expression for the energy!

$$ \omega \Psi(x, t) = \frac{1}{-i}\dfrac{\partial}{\partial t} \Psi(x, t) = i\dfrac{\partial}{\partial t} \Psi(x, t) \quad \Rightarrow \quad \hbar \omega = i\hbar\dfrac{\partial}{\partial t} \Psi(x, t) = E $$

Note: here, we used the fact that $\dfrac{1}{-i} = i$. You can prove this by multiplying $\dfrac{1}{-i}$ by $\dfrac{i}{i}$, which gives you $\dfrac{i}{1} = i$.

Meanwhile, we know that the classical expression for the total energy is given by $E = K + V$, where $K$ is the kinetic energy and $V$ is the potential energy (in quantum mechanics, we often just call this the potential for short). The kinetic energy is related to the momentum $p$ of a classical particle by $K = \mathbf{p}^2/2m$ (where $\mathbf{p}^2 = \mathbf{p} \cdot \mathbf{p}$). This may initially seem relatively useless - we are talking about a quantum particle, not a classical one! - but let's assume that this equation still holds true in the quantum world.

Now, from experiments done in the early 20th-century, we found that all quantum particles have a fundamental quantity known as their de Broglie wavelength (after the French physicist Louis de Broglie who first theorized their existence), which we denote as $\lambda$. This wavelength is tiny - for electrons, $\lambda = \pu{167pm} = \pu{1.67E-10m}$, which is about ten million times smaller than a grain of sand. The momentum of a quantum particle is directly related to the de Broglie wavelength; in fact, it is given by $\mathbf{p} = \hbar \mathbf{k}$, where $|\mathbf{k}| = 2\pi/\lambda$. Combining $\mathbf{p} = \hbar \mathbf{k}$ and $K = \mathbf{p}^2/2m$, we have:

$$ E = K + V = \dfrac{\mathbf{p}^2}{2m} + V(x) = \dfrac{(\hbar \mathbf{k})^2}{2m} + V(x) $$

Can we find another way to relate $\Psi$ and the energy $E$ using this formula? In fact, we can! If we take the gradient of our wavefunction, we have:

$$ \nabla\Psi = \nabla e^{i\mathbf{k} \cdot \mathbf{x}} e^{-i\omega t} = e^{-i\omega t} \nabla e^{i\mathbf{k} \cdot \mathbf{x}}= e^{-i\omega t}i\mathbf{k} (e^{i\mathbf{k} \cdot \mathbf{x}}) = i\mathbf{k} \Psi $$

Then, taking the divergence of the gradient (which is the Laplacian operator $\nabla^2 = \nabla \cdot \nabla$) we have:

$$ \nabla^2 \Psi = (i\mathbf{k})^2 \Psi = -\mathbf{k}^2 \Psi \quad \Rightarrow \quad \mathbf{k}^2 = -\nabla^2 \Psi $$

Combining this with our classical-derived expression for the total energy, we have:

$$ E = \dfrac{(\hbar \mathbf{k})^2}{2m} + V(x) = -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m}\nabla^2 \Psi + V \Psi $$

Where $V \Psi$ is some term that we presume (rightly so) to capture the potential energy of the quantum particle. Equating our two expressions for $E$, we have:

$$ E = i\hbar\dfrac{\partial}{\partial t} \Psi(x, t) = -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} \nabla^2 \Psi + V\Psi $$

Which gives us the Schrödinger equation:

$$ i\hbar\dfrac{\partial}{\partial t} \Psi(x, t) = \left(-\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} \nabla^2 + V\right)\Psi(x,t) $$

What we have been calling $\Psi(x, t)$ can now be properly termed the wavefunction. But what is it? The predominant opinion is that the wavefunction should be considered a probability wave. That is to say, the wave is not a physically-observable quantity! We'll discuss the implications (and consequences) of this in time, but for now, we'll discuss 2 real-valued quantities that can be found

- The amplitude $|\Psi(x, t)|$ is the magnitude of the wavefunction

- The phase $\phi = \text{arg}(\Psi) = \tan^{-1}\left(-\dfrac{\text{Im}(\Psi)}{\text{Re}(\Psi)}\right)$ describes how far along each oscillation the wavefunction has elapsed in space and time. (Here, $\text{arg}$ is the complex-valued argument function.)

Note: In quantum field theory, the probability interpretation of the wavefunction is no longer the case; rather, $\Psi(x, t)$ is reinterpreted as a field and its real and imaginary parts are required to describe both particles and anti-particles. However, we will wait until later to introduce quantum field theory.

The free particle

We already know one basic solution to the Schrodinger equation (in the case $V = 0$): the case of plane waves $e^{i(kx - \omega t)}$. Because the Schrodinger equation is a linear PDE, it is possible to sum several different solutions together to form a new solution; indeed, the integral of a solution is also a solution! Thus, we have arrived at the solution to the Schrodinger equation for a free particle (in one dimension):

$$ \Psi(x, t) = \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \int_{-\infty}^\infty dk~ g(k) e^{i(k x - \omega(k) t)} $$

This is known as a wave packet, since it is a superposition of multiple waves and in fact it looks like a bundle of waves (as shown by the animation below)!

Source: Wikipedia

Reader's note: Another nice animation can be found at this website.

Note that $g(k)$ is an arbitrary function that is determined by the initial conditions of the problem. In particular, using Fourier analysis we can show that it is given by:

$$ g(k) = \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \int_{-\infty}^\infty dx ~\Psi(x, 0) e^{-ikx} $$

In the wave packet solution, $\omega(k)$ is called the dispersion relation and is a fundamental object of study in many areas of condensed-matter physics and diffraction theory. It relates the angular frequency (which governs the time oscillation of the free particle's wavefunction) to the wavenumber (which governs the spatial oscillation of the free particle's wavefunction). The reason we use the angular frequency rather than the "pure" frequency $\nu$ is because $\omega$ is technically the frequency at which the phase of the wavefunction evolves, and complex-exponentials in quantum field theory almost always take the phase as their argument. But what is $\omega(k)$? To answer this, we note that the speed of a wave is given by $v = \omega/k$. For massive particles (e.g. electrons, "massive" here means "with mass" not "very heavy") we can use the formula for the kinetic energy of a free particle, the de Broglie relation $p = \hbar k$ (in one dimension), and the Planck-Einstein relation $E = \hbar \omega$:

$$ K = \dfrac{1}{2} mv^2 = \dfrac{p^2}{2m} = \dfrac{\hbar^2 k^2}{2m} = \hbar \omega $$

Rearranging gives us:

$$ \omega(k) = \dfrac{\hbar k^2}{2m} $$

And thus the wave packet solution becomes:

$$ \Psi_\text{massive}(x, t) = \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \int_{-\infty}^\infty dk~ g(k) e^{i(k x -\frac{\hbar k^2}{2m} t)} $$

By contrast, for massless particles, the result is much simpler: we always have $\omega(k) = kc$ for massless particles in vacuum (the situation is more complicated for particles inside a material, but we won't consider that case for now). Thus the wave packet solution becomes:

$$ \begin{align*} \Psi_\text{massless}(x, t) &= \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \int_{-\infty}^\infty dk~ g(k) e^{i(k x -kc t)} \\ &= \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \int_{-\infty}^\infty dk~ g(k) e^{ik(x-ct)} \end{align*} $$

Note: This is actually identical to the solution of the classical wave equation for an electromagnetic (light) wave, providing us with our first glimpse into how quantum mechanics is related to classical mechanics. The difference is that the quantum wavefunction is a probability wave, whereas the classical wave solution is a physically-measurable wave (that you can actually see!).

Now, let's consider the case where $g(k) = \delta(k - k_0)$, where $k_0$ is a constant and is related to the particle's momentum by $p = \hbar k_0$. This physically corresponds to a particle that has an exactly-known momentum. We'll later see that such particles are actually physically impossible (because of something known as the Heisenberg uncertainty principle that we'll discuss later), but they serve as good mathematical idealizations for simplifying calculations. Placing the explicit form for $g(k)$ into the integral, we have:

$$ \begin{align*} \Psi(x, t) &\approx \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \int_{-\infty}^\infty dk~ \delta(k - k_0) e^{i(k x - \omega t)} \\ &= \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} e^{i(k_0 x - \omega _0 t)}, \quad \omega_0 = \omega(k_0) \end{align*} $$

Note: This comes from the principal identity of the Dirac delta function, which is that $\displaystyle \int_{-\infty}^\infty dx~\delta(x - x_0) f(x) = f(x_0)$.

Where the approximate equality is due to the fact that, again, particles with exactly-known momenta are physically impossible. This is (up to an amplitude factor) the plane-wave solution that we started with, when deriving the Schrödinger equation! From this, we have a confirmation that our derivation is indeed physically-sound and describes (idealized) quantum particles.

Now, let us consider the case where $g(k)$ is given by a Gaussian function:

$$ g(k) = \dfrac{1}{(2\pi)^{1/4} \sigma} e^{-(k-k_0)^2/4\sigma}, \quad \sigma = \text{const.} $$

This may look complicated, but the constant factors are there to simplify calculations. If we substitute this into the integral, this gives us:

$$ \Psi(x, t) = \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi \sigma}} e^{-x^2/\sigma^2}e^{i(k_0 x - \omega_0 t)} $$

This is also a Gaussian function! Notice, however, that our solution now depends on a constant $\sigma$, which controls the "width" of the wave-packet. We will soon learn that it physically corresponds to the uncertainty in position of the quantum particle. Keep this in mind - it will be very important later.

The classical limit of the free particle

Now, let us discuss the classical limit of the wavefunction. We know that $\Psi(x, t)$ describes some sort of probability wave (though we haven't exactly clarified what this probability is meant to represent). We can take a guess though - while quantum particles are waves (and all matter, as far as we know, behave like quantum particles at microscopic scales), classical particles are point-like. This means that they are almost 100% likely to be present at one and exactly one location in space, which is what we classically call the trajectory of the particle. Thus, a classical particle would have the wavefunction approximately given by:

$$ \Psi(x, t) \sim \delta (x - vt) $$

This is a second example of the correspondence principle, which says that in the appropriate limits, quantum mechanics approximately reproduces the predictions of classical mechanics. This is important since we don't usually observe quantum mechanics in everyday life, so it has to reduce to classical mechanics (which we do observe) at macroscopic scales!

Interlude: the Fourier transform

In our analysis of the free quantum particle, we relied on a powerful mathematical tool: the Fourier transform. The Fourier transform allows us to decompose complicated functions as a sum of complex exponentials $e^{\pm ikx}$. It gives us a straightforward way to relate a particle's wavefunction in terms of its possible momenta, and vice-versa.

A confusing fact in physics is that there are actually two common conventions for the Fourier transform. The first convention, often used in electromagnetism, writes the 1D Fourier transform and inverse Fourier transform (in $k$-space, or loosely called frequency space) as:

$$ \tilde f(k) = \dfrac{1}{2\pi} \int_{-\infty}^\infty f(x)e^{-ikx} dx, \quad f(x) = \dfrac{1}{2\pi} \int_{-\infty}^\infty dk \tilde f(k) e^{ikx} $$

Or equivalently, for $N$ spatial dimensions:

$$ f(k) = \dfrac{1}{(2\pi)^N} \int_{-\infty}^\infty d^n k ~\tilde f(x)e^{-i\vec k \cdot \vec x}, \quad f(x) = \dfrac{1}{(2\pi)^N} \int_{-\infty}^\infty d^n k ~\tilde f(k)e^{i\vec k \cdot \vec x} $$

The other convention, more commonly used in quantum mechanics, writes the 1D Fourier transform as:

$$ \tilde f(k) = \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \int_{-\infty}^\infty f(x)e^{-ikx} dx, \quad f(x) = \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \int_{-\infty}^\infty dk \tilde f(k) e^{ikx} $$

The equivalent for $N$ spatial dimensions in this convention is given by:

$$ f(k) = \dfrac{1}{(2\pi)^{N/2}} \int_{-\infty}^\infty d^n k ~\tilde f(x)e^{-i\vec k \cdot \vec x}, \quad f(x) = \dfrac{1}{(2\pi)^{N/2}} \int_{-\infty}^\infty d^n k ~\tilde f(k)e^{i\vec k \cdot \vec x} $$

For reasons we'll see, $k$-space in quantum mechanics is directly related to momentum space. We will stick with the quantum-mechanical convention (unless otherwise stated) for the rest of this guide.

Another look at the wave packet

Recall that our wave packet solution was given by a continuous sum of plane waves, that is:

$$ \Psi(x, t) = \int_{-\infty}^\infty dk~ g(k) e^{i(kx - \omega(k) t)} $$

Note: Throughout this guide we will frequently omit the integration bounds from $-\infty$ to $\infty$ for simplicity. Unless otherwise specified, you can safely assume that any integral written without bounds is an integral over all space (that is, over $-\infty < x < \infty$).

Performing its Fourier transform yields:

$$ \Psi(x, 0) = \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \int g(k) e^{ikx} ~ dk, \quad g(k) = \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \int \Psi(x', 0) e^{-ikx'}dx' $$

Let us verify this calculation by now taking the inverse Fourier transform:

$$ \begin{align*} \Psi(x, 0) &= \dfrac{1}{2\pi} \int dk \int dx' \Psi(x', 0) e^{ik(x - x')} \\ &= \dfrac{1}{2\pi} \int dx' \Psi(x', 0) \underbrace{\int dk e^{ik(x - x')}}_{= 2\pi \delta(x - x')} \\ &= \dfrac{1}{2\pi} \int dx' \Psi(x', 0) [2\pi \delta(x - x')] \\ &= \Psi(x, 0) \end{align*} $$

Where we used the Dirac function identity that $\displaystyle \int f(x')\delta(x - x') dx' = f(x)$ and the fact that the Fourier transform of $e^{ik(x - x')}$ is a delta function.

The Heisenberg uncertainty principle

We're now ready to derive one of the most mysterious results of quantum mechanics: the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. There are a billion different ways to derive it, but the derivation we'll use is a more formal mathematical one (feel free to skip to the end of this section if this is not for you!). To start, we'll use the Bessel-Parseval relation from functional analysis, which requires that:

$$ \int_{-\infty}^\infty dx |\Psi(x, 0)|^2 = 1 = \int dk|g(k)|^2 $$

Using the de Broglie relation $p = \hbar k \Rightarrow k = p/\hbar$ we may perform a change of variables for the integral; using $dk = dp/\hbar$, and thus:

$$ \int dk|g(k)|^2 = \dfrac{1}{\hbar}\int dp|\underbrace{g(k)/\hbar|^2}_{|\tilde \Psi(p)|^2} = 1 $$

This allows us to now write our Fourier-transformed expressions for $\Psi(x, 0)$, which were in position-space (as they depended on $x$), now in momentum space (depending on $p$):

$$ \begin{align*} \underbrace{\Psi(x, 0)}_{\psi(x)} &= \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \hbar}} \int dp~\tilde \psi(p) e^{ipx/\hbar} \\ \tilde \psi(p) &= \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \hbar}} \int dx~ \Psi(x, 0) e^{-ipx/\hbar} \end{align*} $$

Recognizing that $\Psi(x, 0) = \psi(x)$ (the time-independent wavefunction) we may equivalently write:

$$ \begin{align*} \psi(x) &= \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \hbar}} \int dp~\tilde \psi(p) e^{ipx/\hbar} \\ \tilde \psi(p) &= \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \hbar}} \int dx~ \psi(x) e^{-ipx/\hbar} \end{align*} $$

Where $\tilde{\psi}(p)$ (also confusingly often denoted $\psi(p)$) is called the momentum-space wavefunction, and is the Fourier transform of the position-space wavefunction!

Note: It is a common (and extremely confusing!) convention in physics to represent the Fourier transform of a function with the same symbol. That is, it is common to write that the Fourier transform of $\psi(x)$ as simply $\psi(p)$ as opposed to a different symbol (like here, where we use $\tilde \psi(p)$). Due to its ubiquity in physics, we will adopt this convention from this time forward. However, remember that $\psi(x)$ and $\psi(p)$ are actually distinct functions that are Fourier transforms of each other, not the same function!

Exact solutions of the Schrödinger equation

We'll now solve the Schrödinger equation for a greater variety of systems that have exact solutions. Since exact solutions to the Schrödinger equation are quite rare, these are systems that definitely worth studying! To start, recall that the Schrödinger equation reads:

$$ i\hbar \dfrac{\partial}{\partial t} \Psi(x, t) = -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} \nabla^2\Psi + V\Psi $$

Now, the potential $V$ in the Schrödinger equation can be any function of space and time - that is, in general, $V = V(x, t)$. However, in practice, it is much easier to first start by considering only stationary states - that is, time-independent potentials. Thus, the Schrödinger equation now reads:

$$ i\hbar \dfrac{\partial}{\partial t} \Psi(x, t) = -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} \nabla^2\Psi + V(x)\Psi $$

We will now explain a way to write out a general solution of the Schrödinger equation. But how is this possible? The reason why is that the Schrödinger equation is a linear partial differential equation (PDE). Thus, as can be proven in it is possible to sum individual solutions together to arrive at the general solution for the Schrödinger equation for any time-independent problem.

Let us start by assuming that the wavefunction $\Psi(x, t)$ in one dimension can be written as the product $\Psi(x, t) = \psi(x) T(t)$. We can now use the method of separation of variables. To do so, we note that:

$$ \begin{align*} (\nabla^2 \Psi)_\text{1D} &= \dfrac{\partial^2 \Psi}{\partial t^2} = T(t) \dfrac{\partial^2}{\partial x^2} \psi(x) = \psi''(x) T(t) \\ \dfrac{\partial \Psi}{\partial t} &= \psi(x) \dfrac{\partial^2}{\partial t^2} T(t) = \dot T(t) \psi(x) \end{align*} $$

We will now use the shorthand $\psi'' = \psi''(x)$ and $\dot T = \dot T(t)$. Thus the Schrödinger equation becomes:

$$ i\hbar(\psi \dot T) = -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m}\psi'' T + V(x)\psi T $$

If we divide by $\psi T$ from all sides we obtain:

$$ \begin{align*} \dfrac{1}{\psi T} \left[i\hbar(\psi \dot T)\right] &= \dfrac{1}{\psi T}\left[-\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m}\psi'' T + V(x)\psi T\right] = i\hbar \dfrac{\dot T}{T} \\ &= -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} \dfrac{\psi''}{\psi} + V \\ &= E \end{align*} $$

Where $E$ is some constant that we don't know the precise form of yet (if this is not making sense, you may want to review the PDEs guide), and the reason it is a constant is that two combinations of derivatives (here, $\dot T/T$ and $\psi''/\psi$) can only be equal if they are both equal to a constant. Thus, if we multiply through by $\psi$, we have now reduced the problem of finding $\Psi(x, t)$ to solving 2 simpler differential equations:

$$ \begin{align*} -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} \psi'' + V\psi = E\psi \\ i\hbar \dfrac{dT}{dt} = E~ T(t) \end{align*} $$

The second ODE is trivial to solve; its solution is given by plane waves in time, that is, $T(t) \sim e^{-iEt/\hbar}$. The first, however, is not so easy to solve, as we need to know what $V$ is given by, and there are some complicated potentials out there! However, we do know that once we have $\psi(x)$ (often called the time-independent wavefunction since it represents $\Psi(x, t)$ at a "snapshot" in time), then the full wavefunction $\Psi(x)$ is simply:

$$ \Psi(x, t) = \psi(x) e^{-iEt/\hbar} $$

But if $\psi(x)$ is one solution, it must be true that $c_1 \psi(x) + c_2 \psi(x)$ must also be a solution, and thus summing any number of solutions can be used to construct an arbitrary solution. This is what we mean by saying that we have found the general solution to the Schrödinger equation (at least for stationary problems, i.e. $V = V(\mathbf{x})$ and is time-independent) by just summing different solutions together! Thus, solving the ODE for $\psi(x)$ is often called the time-independent Schrödinger equation, and it is given by:

$$ -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} \dfrac{d^2 \psi}{dx^2} + V(x)\psi = E\psi $$

The most general form of the time-independent Schrödinger equation holds in two and three dimensions as well, and is given by:

$$ \left(-\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} \nabla^2 + V(\mathbf{x})\right) \psi = E\psi $$

Consider several solutions $\psi_1, \psi_2, \psi_3, \dots \psi_n$ of the time-independent Schrödinger equation. Due to its linearity (as we discussed previously), a weighted sum of these solutions forms a general solution, given by:

$$ \psi(x) = \sum_{n = 1}^\infty c_n \psi_n(x), \quad c_n = \text{const.} $$

If we back-substitute each individual solution into the time-independent Schrödinger equation, we find that the right-hand side $E$ takes distinct values $E_1, E_2, E_3, \dots E_n$. Using the fact that $\Psi(x, t) = \psi(x) T(t)$, we obtain the most general form of the solution to the Schrödinger equation:

$$ \Psi(x, t) = \sum_{n = 1}^\infty c_n \psi_n(x) e^{-iE_n t/\hbar} \quad \quad c_n, E_n = \text{const.} $$

This solution is very general since does not require us to specify $\psi_n$ and $E_n$; indeed, this general solution is correct for any set of solutions $\psi_n$ of the time-independent Schrödinger equation*. Of course, this form tells us very little about what the $c_n$'s or what the $\psi_n$'s should be. Finding the correct components $c_n$ highly depends on the initial and boundary conditions of the problem, without which it is impossible to determine the form of $\Psi(x, t)$. In the subsequent sections, we will explore a few simple cases where an analytical solution can be found.

*: There are some assumptions underlying this claim, without which it is not strictly true; we'll cover the details later. For those interested in knowing why right away, the reason is that $\Psi(x, t)$ should actually be understood as a vector in an infinite-dimensional space, and $c_n$ are its components when expressed in a particular basis, whose basis vectors are given by $\psi_n$. Since vectors are basis-independent it is possible to write $\Psi(x, t)$ in terms of any chosen basis $\psi_n$ with the appropriate components $c_n$, assuming $\psi_n$ is an orthogonal and complete set of basis vectors.

Bound and scattering states

Solving the Schrödinger equation can be extremely difficult, if not impossible. Luckily, we often don't need to solve the Schrödinger equation to find information about a quantum system! The key is to focus on the potential $V(x)$ in the Schrödinger equation, which tells us that a solution to the Schrödinger equation comes in one of two forms: bound states or scattering states.

Roughly speaking, a bound state is a state where a particle is in a stable configuration, as it takes more energy to remove it from the system than keeping it in place. Meanwhile, a scattering state is a state where a particle is in an inherently unstable configuration, as it takes more energy to keep the particle in place than letting it slip away. Thus, bound states are situations where quantum particle(s) are bound by the potential, while scattering states are situations where quantum particles are unbound and are free to move. A particle in a bound state is essentially trapped in place by a potential; a particle in a scattering state, by contrast, is deflected (but not trapped!) by a potential, a collective phenomenon known as scattering.

At its heart, the difference between a bound state and a scattering state is in the total energy of a particle. A bound state occurs when the energy $E$ of a particle satisfies $E < V$ for all $x$. A scattering state occurs when $E \geq V$ for all $x$. One may show this by doing simple algebraic manipulations on Schrödinger equation. A short sketch of this proof (as explained by Shi, 2025) is as follows. First, note that the Schrödinger equation in one dimension can be rearranged and written in the form:

$$ \dfrac{d^2\psi}{dx^2} = -\dfrac{2m}{\hbar^2} (E - V)\psi = \dfrac{2m}{\hbar^2} (V - E)\psi $$

When $E < V$, the second derivative of the wavefunction is positive for all $x$. This means that at far distances, the Schrödinger equation approximately takes the form $\psi'' \approx \beta^2 \psi$ (where $\beta = \frac{\sqrt{2m}}{\hbar} (V(\infty) - E)$ is approximately a constant). This has solutions for $x > 0$ in terms of real exponentials $e^{-\beta x}$, so the wavefunction decays to infinity and is normalizable, and we have a bound state. Meanwhile, when $E > V$, the second derivative of the wavefunction is negative for all $x$. This means that are far distances, the Schrödinger equation approximately takes the form $\psi'' \approx - \beta^2 \psi$. This has solutions for $x>0$ in terms of complex exponentials $e^{-i\beta x}$, so the wavefunction continues oscillating even at infinity and never decays to zero. This means that the wavefunction is non-normalizable, and we have a scattering state. In theory, the means that scattering-state wavefunctions are unphysical, though in practice we can ignore the normalizability requirement as long as we are aware that we're using a highly-simplified approximation.

Normalizability

To understand another major difference between bound and scattering states, we need to examine the concept of normalizability. Bound states are normalizable states, meaning that they satisfy the normalization condition:

$$ \int_{-\infty}^\infty |\psi(x)|^2 dx = 1 $$

This allows their squared modulus $\rho = |\psi(x)|^2$ to be interpreted as a probability density according to the Born rule. An essential part of a bound state is that it admits solutions to $\hat H \psi = E \psi$ where $E < 0$. This is required for the formation of bound states: the bound-state energy must be negative so that the system is stable.

However, scattering states are not necessarily normalizable. In theory, particles undergoing scattering should be described by wave packets. In practice, this leads to unnecessary mathematical complexity. Instead, it is common to use the non-normalizable states, typically in the form of plane waves:

$$ \psi(x) = A e^{\pm ipx/\hbar} $$

Since these scattering states are not normalizable, $|\psi|^2$ cannot be interpreted as a probability distribution. Instead, they are purely used for mathematical convenience with the understanding that they approximately describe the behavior of particles that have low uncertainty in momentum and thus high uncertainty in position. Of course, real particles are described by wave packets, which are normalizable, but using plane waves gives a good mathematical approximation to a particle whose momentum is close to perfectly-known.

We can in fact show this as follows. Consider a free particle at time $t = 0$, described by the wave packet solution, which we've seen at the beginning of this guide:

$$ \psi(x) = \Psi(x, 0) = \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \hbar}} \int dp'~\overline \Psi(p') e^{ip'x/\hbar} $$

Note: We changed the integration variable for the wavepacket from $p$ to $p'$ to avoid confusion later on. The integral expressions, however, are equivalent.

Now, assume that the particle's momentum is confined to a small range of values, or equivalently, has a low uncertainty in momentum. We can thus make the approximation that $\overline \Psi(p') \approx \delta(p - p')$, where $p$ is the particle's momentum. Thus, performing the integration, we have:

$$ \psi(x) \approx \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \hbar}} \int dp'~ \delta(p - p') e^{ip'x/\hbar} \sim \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} e^{ipx/\hbar} $$

This is exactly a plane wave in the form $\psi(x) = Ae^{ipx/\hbar}$, and a momentum eigenstate! Thus we come to the conclusion that while momentum eigenstates $\psi \sim e^{\pm ipx/\hbar}$ are non-normalizable and thus unphysical, they are a good approximation for describing particles with low uncertainty in momentum.

Likewise, wavefunctions of the type $\psi(x) \sim \delta(x-x_0)$ are also unphysical, and are just mathematical approximations to highly-localized wavepackets, where the particles' uncertainty in position is very small. Thus, we conclude that eigenstates of the position operator (which are delta functions) are also non-normalizable, which makes sense, since there is no such thing as a particle with exactly-known position (or momentum!).

The particle in a box

We will now consider our first example of a bound state: a quantum particle confined within a small region by a step potential, also called the particle in a box or the square well. Despite its (relative) simplicity, the particle in a box is the basis for the Fermi gas model in solid-state physics, so it is very important! (It is also used in describing polymers, nanometer-scale semiconductors, and quantum well lasers, for those curious), for those curious). The particle in a box is described by the potential:

$$ \begin{align*} V(x) = \begin{cases} V_0, & x < 0 \\ 0, & 0 \leq x \leq L \\ V_0, & x > L \end{cases} \end{align*} $$

Note: it is often common to use the convention that $V = 0$ for $x < 0$ and $x > L$ and $V = -V_0$ in the center region ($0 \leq x \leq L$). These two are entirely equivalent since they differ by only a constant energy ($V_0$) and we know that adding a constant to the potential does not change any of the physics.

We show a drawing of the box potential below:

We assume that the particle has energy $E < V_0$, meaning that it is a bound state and the particle is contained within the well. To start, we'll only consider the case where $V_0 \to \infty$, often called an infinite square well. This means that the particle is permanently trapped within the well and cannot possibly escape. In mathematical terms, it corresponds to the boundary condition that:

$$ \begin{align*} \psi(x) \to 0, \quad x < 0 \\ \psi(x) \to 0, \quad x> L \end{align*} $$

Equivalently, we can write these boundary conditions in more standard form as:

$$ \psi(0) = \psi(L) = 0 $$

In practical terms, it simplifies our analysis so that we need only consider a finite interval $0 \leq x \leq L$ rather than the infinite domain $-\infty < x < \infty$, simplifying our normalization requirement.

Solving the Schrödinger equation for the infinite square well

To start, we'll use the tried-and-true method to first assume a form of the wavefunction as:

$$ \psi(x) = Ae^{ikx} + A' e^{-ikx} $$

Where $A$ is some normalization faction that we will figure out later. This may seem unphysical (since it's made of plane waves), but it is not actually so. The reason why is that if we pick $A' = -A$, Euler's formula $e^{i\phi} = \cos \phi + i\sin \phi$ tells us that:

$$ \begin{align*} \psi(x) &= Ae^{ikx} - Ae^{-ikx} \\ &= A(e^{ikx} - e^{-ikx}) \\ &= A(\cos k x + i \sin k x - \underbrace{\cos (-kx)}_{\cos(-\theta) = \cos \theta} - \underbrace{i\sin(-kx)}_{\sin(-\theta) = -\sin \theta}) \\ &= A (\cos kx - \cos k x + i \sin k x - (-i \sin k x)) \\ &= A (i\sin kx + i\sin k x + \cancel{\cos k x - \cos k x}^0) \\ &= \beta\sin k x, \qquad \beta = 2A i \end{align*} $$

We notice that $\psi(x) \sim \sin(kx)$ automatically satisfies $\psi(0) = 0$, which tells us that we're on the right track! Additionally, since cosine is a bounded function over a finite interval, we know it is a normalizable (and thus physically-possible) solution. However, we still need to find $k$ and the normalization factor $\beta = 2Ai$, which is what we'll do next.

Let's first start by finding $k$. Substituting our boundary condition $\psi(L) = 0$, we have:

$$ \psi(L) = \beta \sin(k L) = 0 $$

Since the sine function is only zero at intervals of $n\pi = 0, \pi, 2\pi, 3\pi, \dots$ (where $n$ is an integer), our above equation can only be true if $kL = n\pi$. A short rearrangement then yields $k = n\pi/L$, and thus:

$$ \psi(x) = \beta \sin \dfrac{n\pi}{L} $$

To find $\beta$, we use the normalization condition:

$$ \begin{align*} 1 &= \int_{-\infty}^\infty \psi(x)\psi^* (x) dx \\ &= \underbrace{\int_{-\infty}^0 \psi(x)^2 dx}_{0} + \int_{0}^L \psi(x)^2 dx + \underbrace{\int_L^\infty \psi(x)^2 dx}_0 \\ &= \underbrace{-4A^2}_{\beta^2} \int_{0}^L \sin^2 \left(\dfrac{n\pi x}{L}\right)dx \\ &= A^2 L/2 \end{align*} $$

Where we used the integral property:

$$ \int_a^b \sin^2 \beta x = \left[\dfrac{x}{2} - \dfrac{\sin(2\beta x)}{4\beta}\right]_a^b $$

From our result, we can solve for $A$:

$$ A^2 L/2 = 1 \quad \Rightarrow \quad A = \sqrt{\dfrac{2}{L}} $$

From which we obtain our position-space wavefunctions:

$$ \psi(x) = \sqrt{\frac{2}{L}} \sin \left(\dfrac{n\pi x}{L}\right), \quad n =1, 2, 3, \dots $$

We note that a solution is present for every value of $n$. This means that we have technically found an infinite family of solutions $\psi_1, \psi_2, \psi_3, \dots, \psi_n$, each parameterized by a different value of $n$. We show a few of these solutions in the figure below:

Source: ResearchGate. Note that the vertical position of the different wavefunctions is for graphical purposes only.

Energy of particle in a box

Now that we have the wavefunctions, we can solve for the possible values of the energies. We can find this by plugging in our solution into the time-independent Schrödinger equation:

$$ -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m}\dfrac{d^2 \psi}{dx^2} = E \psi(x) $$

Upon substituting, we have:

$$ \begin{align*} -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m}\dfrac{d^2 \psi}{dx^2} &= -\frac{\hbar^2}{2m} \left(-\frac{n^2 \pi^2}{L^2}\right) \sqrt{\dfrac{2}{L}} \sin \dfrac{n\pi x}{L} \\ &= \underbrace{\dfrac{n^2 \pi^2 \hbar^2}{2mL^2} \psi(x)}_{E \psi} \end{align*} $$

From which we can easily read off the energy to be:

$$ E_n = \dfrac{n^2 \pi^2 \hbar^2}{2mL^2}, \quad n = 1, 2, 3, \dots $$

We find that the particle always has a nonzero energy, even in its ground state. The lowest energy is called its ground-state energy, and the reason it is nonzero is that the energy-time uncertainty principle forbids a particle to have zero energy.

Note for the advanced reader: Quantum field theory gives the complete explanation for why a particle can have nonzero energy even in its ground state. The reason is that the vacuum in quantum field theory is never empty; spontaneous energy fluctuations in the vacuum lead to a nonzero energy even in the ground state, and it would take an infinite amount of energy (or equivalently, infinite time) to suppress all of these fluctuations.

The rectangular potential barrier

We will now tackle solving our first scattering-state problem, the famous problem of the particle at a potential barrier (which is a simple model that can be used to model, among other things, the mechanics of scanning electron microscopes). In this example, a quantum particle with energy $E$ is placed at some position in a potential given by:

$$ V(x) = \begin{cases} 0 & x < 0 \\ V_0 & x > 0 \end{cases}, \quad E > V $$

(Note that the discontinuity in the potential at $x = 0$ is unimportant to the problem, although it is convenient to define $V(0) = V_0/2$). You can think of this as a quantum particle hitting a quantum "wall" of sorts; the potential blocks its path and changes its behavior, although what the particle does next defies classical intuition completely.

To solve this problem, we split it into two parts. For the first part, we assume that the particle initially starts from the left (that is, $x = -\infty$) and moves towards the right. This means that the particle can only be found at $x < 0$. Then, the particle's initial wavefunction can (approximately) be represented as a free particle with a plane wave:

$$ \psi_I(x) = e^{ikx}, \quad x < 0, \quad k = \frac{p}{\hbar} = \dfrac{\sqrt{2mE}}{\hbar} $$

Where $\psi_I$ denotes the initial wavefunction (that is, the particle's wavefunction when it starts off from far away), and $k$ comes from $p = \hbar k$ and $E = p^2/2m$. We say "approximately" because we know that real particles are wavepackets, not plane waves (since plane waves are unphysical, as we have seen before); nevertheless, it is a suitable approximation for our case. We can also write the initial wavefunction in the following equivalent form:

$$ \psi_I(x) = \begin{cases} e^{ikx}, & x < 0 \\ 0, & x> 0 \end{cases} $$

Note on notation: It is conventional to use positive-phase plane waves $e^{ikx}$ to describe right-going particles and negative-phase plane waves $e^{-ikx}$ to describe left-going particles.

Now, when the particle hits the potential barrier "wall", you may expect that the particle stops or bounces back. But remember that since quantum particles are probability waves, they don't behave like classical particles. In fact, what actually happens is that they partially reflect (go back to $x \to -\infty$) and partially pass through (go to $x \to \infty$)! This would be like a person walking into a wall, then both passing through and bouncing back from the wall, which is truly bizarre from a classical point of view. However, it is perfectly possible for this to happen in the quantum world!

Note: This analogy is a bit oversimplified, because quantum particles are ultimately probability waves and it is not really the particle that "passes through" the "wall" but rather its wavefunction that extends both beyond and behind the potential barrier "wall". When we actually measure the particle, we don't find it "midway" through the wall; instead, we sometimes find that it is behind the wall, and at other times find that it is ahead of the wall. What is significant here is that there is a nonzero probability of the particle passing through the potential barrier, even though classical this is impossible.

Since the particle can (roughly-speaking) exhibit both reflection (bouncing back from the potential barrier and traveling away to $x \to -\infty$) and transmission (passing through the potential barrier and traveling to $x \to \infty$), its final wavefunction would take the form:

$$ \psi_F = \begin{cases} r e^{-ikx}, & x < 0 \\ te^{ik'x}, & x > 0 \end{cases} $$

Where $k'$ is the momentum of the particle if it passes through the barrier, since passing through the potential barrier saps some of its energy; mathematically, we have:

$$ k = \dfrac{\sqrt{2mE}}{\hbar}, \quad k' = \dfrac{\sqrt{2m(V_0 - E)}}{\hbar} $$

The total wavefunction is the sum of the initial and final wavefunctions, and is given by:

$$ \psi(x) = \psi_I + \psi_F = \begin{cases} e^{ikx} + r e^{-ikx}, & x < 0 \\ te^{ik'x}, & x > 0 \end{cases} $$

The coefficients $r$ and $t$ are the reflection coefficient and transmission coefficient respectively. This is because they represents the amplitudes of the particle reflecting and passing through the barrier. We also define the reflection probability $R$ and transmission probability $T$ as follows:

$$ R = |r|^2,\quad R + T = 1 $$

Note: The reason why $R + T = 1$ is because the particle cannot just whizz off or disappear after hitting the potential barrier; it must either be reflected or pass through, so conservation of probability tells us that $R + T = 1$.

To be able to solve for what $r$ and $t$ should be, we first use the requirement that the wavefunction is continuous at $x = 0$. Why? Mathematically, this is because the Schrödinger equation is a differential equation, and the derivative of a function is ill-defined if the wavefunction is not continuous. Physically, this is because any jump in the wavefunction means that the probability of finding a particle in two adjacent areas in space abruptly changes without any probability of finding the particle somewhere in between, which, again, does not make physical sense. This means that at $t = 0$, the left ($x < 0$) and right ($x > 0$) branches of the wavefunction must be equal, or in other words:

$$ \begin{gather*} e^{ikx} + r e^{-ikx} = te^{ik'x}, \quad x = 0 \\ e^0 + r e^0 = te^0 \\ 1 + r = t \end{gather*} $$

Additionally, the first derivatives of the left and right branches of the wavefunctions must also match for the first derivative to be continuous. After all, the Schrödinger equation is a second-order differential equation in space, so for the second derivative to exist, the first derivative must also be continuous. Thus we have:

$$ \begin{align*} \dfrac{\partial \psi}{\partial x}\bigg|_{x < 0} &= \dfrac{\partial \psi}{\partial x}\bigg|_{x > 0}, \quad x = 0 \\ ik e^{ikx} - ikre^{-ikx} &= ik' te^{ik'x}, \quad x = 0 \\ ik - ikr &= ik' t \\ k(1 - r) &= k' t \end{align*} $$

Using these two equations, we can now find $r$ and $t$ explicitly. If we substitute $1 + r = t$, we can solve for the transmission coefficient $t$:

$$ \begin{gather*} k(1 - r) = k't = k'(1 + r) \\ k - kr = k' + k' r \\ k - k' = k'r + kr \\ k - k' = r(k + k') \\ r = \dfrac{k - k'}{k + k'} \end{gather*} $$

Thus, we can now find the reflection probability, which is the probability the particle will be reflected after "hitting" the potential barrier:

$$ R = |r|^2 = \left(\dfrac{k - k'}{k + k'}\right)^2 $$

(Note that since $k, k'$ are real-valued, $|r|^2 = r^2$). We can also find the transmission coefficient $t$ from $t = 1+ r$:

$$ \begin{align*} t &= 1 + r \\ &= 1 + \dfrac{k - k'}{k + k'} \\ &= \dfrac{k + k'}{k + k'} + \dfrac{k - k'}{k + k'} \\ &= \dfrac{k + k + \cancel{k' - k'}}{k + k'} \\ &= \dfrac{2k}{k + k'} \end{align*} $$

Thus we can calculate the transmission probability:

$$ T = 1 - R = \dfrac{4kk'}{(k + k')^2} $$

The state-vector and its representations

In quantum mechanics, we have said that particles are probabilistic waves rather than discrete objects. This is actually only a half-truth. The more accurate picture is that quantum particles are represented by vectors in an complex space. "What??", you might say. But however strange this may first appear to be, recognizing that particles are represented by vectors is actually crucial, particularly for more advanced quantum physics (e.g. quantum field theory).

The fundamental vector describing a particle (or more precisely, a quantum system) is called the state-vector, and is written in the rather funny-looking notation $|\Psi\rangle$. This state-vector is not particularly easy to visualize, but one can think of it as an "arrow" of sorts that points not in real space, but in a complex space. As a particle evolves through time, it traces something akin to a "path" through this complex space. Unlike the vectors we might be used to, which live in $\mathbb{R}^3$ (t/hat is, Euclidean 3D space), this complex space (formally called a Hilbert space $\mathcal{H}$) can be of any number of dimensions!

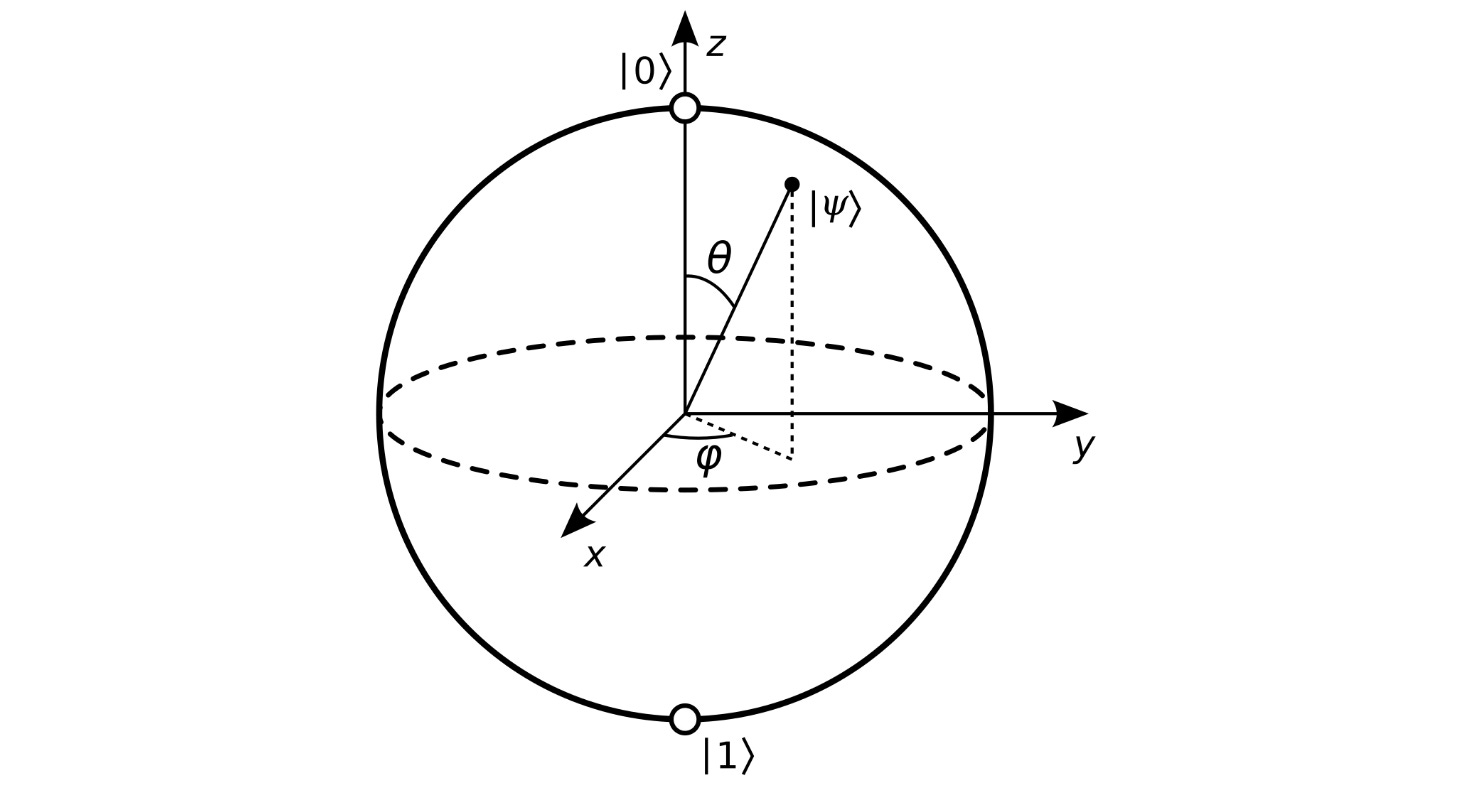

Of course, visualizing all those dimensions in a Hilbert space is next to impossible. However, if we consider only two (complex) dimensions, the state-vector might look something like this:

Credit: Dr. Ashish Bamania

Why is this drawn in 3D? The reason is that each complex dimension is not an axis (as would be the case for real dimensions), but rather a complex plane. This is why a two-dimensional complex space is drawn in 3D, not 2D - it is formed by taking two complex planes and placing them at 90 degrees to each other, so it has to stretch into 3D.

To practice, let's consider a complex space with three dimensions, which we'll call $x$ and $y$ (though remember, these dimensions are not the physical $x,y,z$ axes). A 3-dimensional complex space is unfortunately not easily drawn, but it is simple enough that the calculations don't get too hairy!

Now, like the vectors we might be used to, like the position vector $\mathbf{r} = \langle x, y, z\rangle$ or momentum vector $\mathbf{p} = \langle p_x, p_y, p_z\rangle$, the state-vector also has components, although (as we discussed) these components are in general complex numbers that have no relationship to the physical $x, y, z$ axes. For our three-dimensional example, we can write the state-vector $|\Psi\rangle$ in column-vector form as follows:

$$ |\Psi\rangle = \begin{pmatrix} c_1 \\ c_2 \\ c_3 \end{pmatrix}, \quad c_i \in \mathbb{C} $$

We might ask whether there is a row-vector form of a state-vector, just like classical vectors have, for instance, $\mathbf{r}^T$ and $\mathbf{p}^T$ as their row-vector forms (their transpose). Indeed there is an equivalent of the row-vector form for state-vectors, which we'll write as $\langle \Psi|$ (it can seem to be a funny notation but is actually very important). $\langle \Psi|$ can be written in row-vector form as:

$$ \langle \Psi| = \begin{pmatrix} c_1^* & c_2^* & c_3^* \end{pmatrix} $$

Note: Formally, we say that $\langle \Psi|$ is called the Hermitian conjugate of $|\Psi\rangle$, and is just a fancy name for taking the transpose of the state-vector and then complex-conjugating every component. We will see this more later.

We now might wonder if there is some equivalent of the dot product for a state-vector, just like classical vectors can have dot products. Indeed, there is, although we call it the inner product as opposed to the dot product. The standard and also quite funny-looking notation is to write the inner ("dot") product of $\langle \Psi|$ and $|\Psi\rangle$ as $\langle \Psi|\Psi\rangle$, which is written as:

$$ \begin{align*} \langle \Psi|\Psi\rangle &= \begin{pmatrix} c_1^* & c_2^* & c_3^* \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} c_1 \\ c_2 \\ c_3 \end{pmatrix} \\ &= c_1 c_1^* + c_2 c_2^* + c_3 c_3^* \\ &= |c_1|^2 + |c_2|^2 + |c_3|^2 \end{align*} $$

In quantum mechanics, we impose the restriction that $\langle \Psi|\Psi\rangle = 1$, which also means that $|c_1|^2 + |c_2|^2 + |c_3|^2 = 1$. This is the normalization condition. Indeed, it looks suspiciously-similar to our previous requirement of normalizability in wave mechanics:

$$ \langle \Psi|\Psi\rangle = 1 \quad \Leftrightarrow \quad \int_{-\infty}^\infty \psi(x) \psi^*(x) dx = 1 $$

We'll actually find later that - surprisingly - these are equivalent statements!

Basis representation of vectors

Let's return to our state-vector $|\Psi\rangle$, which we wrote in the column vector form as:

$$ |\Psi\rangle = \begin{pmatrix} c_1 \\ c_2 \\ c_3 \end{pmatrix}, \quad c_i \in \mathbb{C} $$

Is there another way that we can write out $|\Psi\rangle$? Indeed there is! Recall that in normal space, vectors can also be written as a linear sum of basis vectors. This is also true in quantum mechanics and complex-valued spaces! For instance, we can write it out as follows:

$$ |\psi\rangle = c_1 \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} + c_2 \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} + c_3 \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix} $$

Here, $(1, 0, 0)$, $(0, 1, 0)$, and $(0, 0, 1)$ are the basis vectors we use to write out the state-vector in basis form - together, we call them a basis (plural bases). We can make this more compact and general if we define:

$$ \begin{align*} |u_1\rangle &= \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \\ |u_2\rangle &= \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \\ |u_3\rangle &= \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix} \end{align*} $$

Then, the linear sum of the three basis vectors can be written as follows:

$$ |\psi\rangle = c_1 |u_1\rangle + c_2 |u_2\rangle + c_3 |u_3\rangle $$

A basis must be orthonormal, which means that its set of basis vectors are normalized and are orthogonal to each other. That is to say:

$$ \langle u_i |u_j\rangle = \begin{cases} 1, & |u_i\rangle = |u_j\rangle \\ 0, & |u_i\rangle \neq |u_j\rangle \end{cases} $$

A basis must also be complete. This means that any vector in a particular space can be written as a sum of the basis vectors (with appropriate coefficients). In intuitive terms, you can arrange the basis vectors in such a way that they can form any vector you want. For instance, in the below diagram, a vector $\mathbf{u} = (2, 3, 5)$ is formed by the sum of vectors $\mathbf{v}_1$ and $\mathbf{v}_2$:

Source: Ximera

A complete basis is required because otherwise, the space cannot be fully described by the basis vectors; there are mysterious "unreachable vectors" that exist but are "out of reach" of the basis vectors. This leads to major problems when we want to actually do physics with basis vectors, so we always want a complete basis in quantum mechanics. The set of all basic vectors in the basis is called the state space of the system, and physically represents all the possible states the system can be in - we'll discuss more on this later.

Having a complete and orthonormal basis allows us to expand an arbitrary vector $|\varphi\rangle$ in the space in terms of the basis vectors of the space:

$$ |\varphi\rangle = \sum_i c_i |u_i\rangle $$

Where $c_i = \langle u_i|\varphi\rangle$ is the probability amplitude of measuring the $|u_i\rangle$ state. The reason we call it a probability amplitude rather than the probability itself is that $c_i$ is in general complex-valued. To get the actual probability (which we denote as $\mathcal{P}_i$), we must take its absolute value (complex norm) and square it:

$$ \mathcal{P}_i = |c_i|^2 = c_i c_i^* $$

Note that this guarantees that the probability is real-valued, since the complex norm $|z|$ of any complex number $z$ is real-valued. Now, all of this comes purely from the math, but let's discuss the physical interpretation of our results. In quantum mechanics, we assign the following interpretations to the mathematical objects from linear algebra we have discussed:

- The state-vector $|\Psi\rangle$ contains all the information about a quantum system, and "lives" in a vector space called a Hilbert space (we often just call this a "space")

- Each basis vector $|u_i\rangle$ in the Hilbert space represents a possible state of the system; thus, the set of all basis vectors represents all possible states of the system, which is why basis vectors must span the space

- The set of all basis vectors is called the state space of the system and describes how many states the quantum system has

- The state-vector is a sum of the basis vectors of the space, since quantum systems (unlike classical systems) are probabilistic mixtures of different states; which particular state the system is in cannot be determined without measuring (and fundamentally disrupting) the quantum system

- The probability of measuring the $i$-th state of the system is given by $\mathcal{P}_i = |c_i|^2$, where $c_i = \langle u_i|\Psi\rangle$

The outer product

We have already seen one way to take the product of two quantum-mechanical vectors, that being the inner product. But it turns out that there is another way to take the product of two vectors in quantum mechanics, and it is called the outer product. The outer product between two vectors $|\alpha\rangle, |\beta\rangle$ is written in one of two ways:

$$ |\beta\rangle \langle \alpha |\quad \Leftrightarrow \quad |\beta\rangle \otimes \langle \alpha| $$

(Note that the $|\beta\rangle \langle \alpha|$ notation is the most commonly used). The outer product is quite a bit different from the inner product because instead of returning a scalar, it returns a matrix. But how do we compute it? Well, if $|\alpha\rangle$ and $|\beta\rangle$ are both three-component quantum vectors (which means they can be complex-valued) their outer product is given by:

$$ \begin{align*} |\beta\rangle \langle \alpha| &= \begin{pmatrix} \beta_1^* \\ \beta_2^* \\ \beta_3^* \end{pmatrix}^T \otimes \begin{pmatrix} \alpha_1 \\ \alpha_2 \\ \alpha_3 \end{pmatrix} \\ &= \begin{pmatrix} \alpha_1 \beta_1^* & \alpha_1 \beta_2^* & \alpha_1 \beta_3^* \\ \alpha_2 \beta_1^* & \alpha_2 \beta_2^* & \alpha_2 \beta_3^* \\ \alpha_3 \beta_1^* & \alpha_3 \beta_2^* & \alpha_3 \beta_3^* \end{pmatrix} \end{align*} $$

In general, for two vectors $|\alpha\rangle, |\beta\rangle$ the matrix $C_{ij} = (|\beta\rangle \langle \alpha|)_{ij}$ has components given by:

$$ (|\beta\rangle \langle \alpha|)_{ij} = C_{ij} = \alpha_i \beta_j^* $$

For instance, if we use this formula, the $C_{11}$ component is equal to $\alpha_1 \beta_1^*$, and the $C_{32}$ component is equal to $\alpha_3 \beta_2^*$. The outer product is a bit hard to understand in intuitive terms, so it is okay at this point to just think of the outer product as an operation that takes two vectors and gives you a matrix, just like the inner product takes two vectors and gives you a scalar.

Note: For those familiar with more advanced linear algebra, the outer product is formally the tensor product of a ket-vector and a bra-vector; in tensor notation one can use the alternate notation with $C_i{}^j = \alpha_i \beta^j$ which shares a correspondence with relativistic tensor notation. Another interesting article to read is this Math StackExchange explanation of the outer product.

The outer product is very important because, among other reasons, it is used to express the closure relation of any vector space:

$$ \sum_i |u_i\rangle \langle u_i | = \hat I $$

Where here, $\hat I$ is the identity matrix, and $|u_i\rangle$ are the basis vectors. What does this mean? Remember that the outer product of two vectors creates a matrix. The closure relation tells us that the sum of all of these matrices - formed from the basis vectors - is the identity matrix $\hat I$. Roughly speaking, this means that summing all the possible matrices formed by basis vectors allows you to get the identity matrix. This is essentially an equivalent restatement of our previous definition of completeness, which tells us that the set of basis vectors must span the space and thus any arbitrary vector can be expressed as a sum of basis vectors. This is because, assuming an arbitrary vector $|\varphi\rangle$:

$$ \begin{align*} |\varphi\rangle &= |\varphi\rangle \\ &= \hat I |\varphi\rangle \\ &= \sum_i |u_i\rangle \underbrace{\langle u_i|\varphi\rangle}_{c_i} \\ &= \sum_i c_i |u_i\rangle \end{align*} $$

Thus we find that indeed, the closure relation tells us that an arbitrary vector $|\varphi\rangle$ can be expressed as a sum of basis vectors, which is just the same thing as the requirement that the basis vectors be complete and orthonormal.

Note: It is also common to use the notation $\sum_i |c_i\rangle \langle c_i| = 1$ for the closure relation, with the implicit understanding that $1$ means the identity matrix.

Interlude: classifications of quantum systems

In quantum mechanics, we use a variety of names to describe different types of quantum systems. There are a lot of different terms we use, but let's go through short number of them. First, we may encounter finite-dimensional systems or infinite-dimensional systems. Here, dimension refers to the dimension of the state space, not the dimensions in 3D Cartesian space. A finite-dimensional system is spanned by a finite number of basis vectors. This means that the system can only be in a finite number of states. An analogy is that of a perfect coin toss: a coin can only be heads-up or heads-down. If we use quantum mechanical notation and denote $|h\rangle$ as the heads-up state and $|d\rangle$ as the heads-down state, we can write the "state-vector" of the coin as:

$$ |\psi\rangle_\text{coin} = c_1 |h\rangle + c_2 |d\rangle $$

Where $c_1, c_2$ are the probability amplitudes of measuring the heads-up and heads-down states respectively. Since we know the probability is found by squaring the probability amplitudes, the probability of measuring the coin to be heads-up is $\mathcal{P}_1 = |c_1|^2$ and likewise the probability of measuring the coin to be heads-down is $\mathcal{P}_2 = |c_2|^2$. We know that a (perfect) coin toss is equally likely to be heads-up and heads-down, or in otherwise, there is a 50% probability for either heads-up or heads down, and thus $\mathcal{P}_1 = \mathcal{P}_2 = 1/2$, so we have $c_1 = c_2 = 1/\sqrt{2}$. This gives us:

$$ |\psi\rangle_\text{coin} = \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}} |h\rangle + \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}} |d\rangle $$

An infinite-dimensional system, by contrast, is spanned by an infinite number of basis vectors. This means that the system can (in principle) be in an infinite number of states. For instance, consider a free quantum particle moving along a line: its position is unconstrained, so it can be in any position $x \in (-\infty, \infty)$. Thus, there are indeed an infinite number of states $|x_1\rangle, |x_2\rangle, |x_3\rangle, \dots, |x_n\rangle$ (corresponding to positions $x_1, x_2, x_3, \dots, x_n$) that the particle can be in. The particle in a box is also an infinite-dimensional system, since it also has an infinite number of possible states (recall that the eigenstates can be written in the form $\psi_n(x)$, where $n$ can be arbitrarily large).

Another distinction between quantum systems is between continuous systems and discrete systems. A discrete system has basis vectors with discrete eigenvalues, while a continuous system has basis vectors with continuous eigenvalues. For instance, momentum basis vectors $|p_1\rangle,|p_2\rangle, |p_2\rangle$ have continuous eigenvalues, since the possible values of a particle's momentum can (usually) be any value. However, the vast majority of bases we use in quantum mechanics do not have continuous eigenvalues, and can only take particular values. In fact, the "quantum" in quantum mechanics refers to the fact that a measurement on a quantum particle frequently yields discrete results that are multiples of a fundamental value, called a quanta.

Note: It is important to note that an infinite-dimensional system may still be a discrete system. For instance, the eigenstates of the particle in a box form an infinite-dimensional state space, but as they have discrete (energy) eigenvalues, the system is still discrete.

Differentiating between discrete and continuous systems - as well as between finite-dimensional and infinite-dimensional systems - is very important! This is because they change the way key identities are defined. For instance, in a continuous system, we can write the closure relation as:

$$ \int |\alpha\rangle \langle \alpha| d\alpha = 1 $$

And likewise, one can write out the basis expansion as:

$$ |\psi\rangle = \int c(\alpha)|\alpha\rangle d\alpha $$

Meanwhile, for a discrete system, the basis expansion instead takes the form:

$$ |\psi\rangle = \sum_\alpha c_\alpha |\alpha\rangle $$

And the closure relation is given by:

$$ \sum_\alpha |\alpha \rangle \langle \alpha| = 1 $$

The crucial thing here is that these expressions are extremely general - they work for any set of continuous basis vectors (for a continuous system) or discrete basis vectors (for a discrete system). It doesn't matter which basis we use!

Quantum operators

In classical mechanics, physical quantities like energy, momentum, and velocity are all given by functions (typically of space and of time). For instance, the total energy of a system (more formally known as the Hamiltonian, see the guide to Lagrangian and Hamiltonian mechanics for more information), is given by a function $H(x, p, t)$, where $x(t)$ is the position of the particle and $p(t)$ is its momentum (roughly-speaking). However, in quantum mechanics, each physical quantity is associated with an operator instead of a function. For instance, there is the momentum operator $\hat p$, the position operator $\hat x$, and the Hamiltonian operator $\hat H$, where the hats (represented by the symbol $\hat{}$) tell us that these are operators, not functions.

So what is an operator? An operator is something that takes one vector (or function) and transforms it to another vector (or function). A good example of an operator is a transformation matrix. Applying a transformation matrix on one vector gives us another vector, which is exactly what an operator does. One can also define operators that operate on vectors instead of functions (as a consequence, they are usually differential operators, meaning that they return some combination of the derivative(s) of a function). Some of these include the position operator ($\hat x$), momentum operator ($\hat p$), the kinetic energy operator $\hat K$, and the potential energy operator $\hat V$. They respectively have the forms:

$$ \begin{align*} \hat x &= x \\ \hat p &= -i\hbar \nabla \\ \hat K &= \frac{\hat p^2}{2m} = -\frac{\hbar^2}{2m} \nabla^2 \\ \hat V &= V(\mathbf{x}) \end{align*} $$

Combining the kinetic and potential energy operators gives us the total energy (or Hamiltonian) operator ($\hat H$):

$$ \hat H = \hat K + \hat V = -\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m} \nabla^2 + V $$

Eigenstates of the momentum operator

For some operators, it is straightforward to find their eigenstates. For instance, if we simply solve the eigenvalue equation for the momentum operator, we have:

$$ \hat p \psi = i\hbar \dfrac{\partial \psi}{\partial x} = p \psi $$

This differential equation has the straightforward solution $\psi(x) = e^{\pm ipx/\hbar}$, which is just a plane wave. Of course, momentum eigenstates are physically cannot exist, because real particles, of course, have to be somewhere, and by the Heisenberg uncertainty relation a pure momentum eigenstate means a particle can be anywhere! However, they are a good approximation in many cases to particles with a very small range of momenta.

Eigenstates of the position operator

Similarly, the position operator's eigenstates can also be found if we write out its eigenvalue equation:

$$ \hat x \psi = x' \psi $$

Where $x'$ is some eigenvalue of the position operator. The only function that satisfies this equation is the Dirac delta "function":

$$ \psi = a\delta(x - x'), \quad a = \text{const.} $$

Eigenstates of the Hamiltonian

The Hamiltonian operator's eigenstates can also be found through its eigenvalue equation:

$$ \hat H \psi = \left(-\dfrac{\hbar^2}{2m}\nabla^2 + V(x)\right)\psi = E \psi $$

Notice how this is the same thing as the time-independent Schrödinger equation! Thus, the eigenstates of the Hamiltonian are the solutions to the time-independent Schrödinger equation, and the eigenvalues are the possible energies of the system.

Generalized operators in bra-ket notation

Up to this point, we have seen operators only in wave mechanics. Let us now generalize the notion of an operator on the state-vector, which (as we know) is the more fundamental quantity. In bra-ket notation an operator $\hat A$ is written as:

$$ \hat A|\psi\rangle = |\psi'\rangle $$

In quantum mechanics, for the most part, we only consider linear operators. The formal definition of a linear operator is that the operator satisfies:

$$ \hat A(\lambda_1 |\psi_1\rangle + \lambda_2 |\psi_2\rangle) = \lambda_1 \hat A|\psi_1\rangle + \lambda_2 |\hat \psi_2\rangle $$

As a consequence, all linear operators also satisfy:

$$ (\hat A \hat B) |\psi\rangle = \hat A(\hat B |\psi\rangle) $$

Likewise, "sandwiching" a linear operator between a bra $|\psi\rangle$ and a ket $\langle \varphi|$ always produces a scalar $c$:

$$ \langle \varphi| \hat A |\psi \rangle = \langle \varphi|(\hat A |\psi\rangle)) = c $$

Note: The scalar $c$ is frequently called in the literature as a c-number (short for "complex number"). This is to distinguish it from vectors, matrices, and operators in quantum mechanics, which are not scalars (even if they are complex-valued).

A frequent use of this "sandwiching" is to calculate the expectation value of an operator. The expectation value of a (physically-relevant) operator $\hat A$, denoted $\langle \hat A\rangle$, is the mean measured value of the physical quantity the operator represents. That is to say, if we had a quantum system described by a state-vector $|\Psi\rangle$, and we wanted to measure a certain quantity that is associated with an operator $\hat A$, then the expectation value is the averaged value of repeatedly measuring the system. Mathematically, the expression for the expectation value is given by:

$$ \langle A\rangle = \langle \Psi|\hat A|\Psi\rangle $$

Note: the expectation value of a vector operator $\mathbf{A}$ (for instance, the 3D position operator or 3D momentum operator) is a vector of its expectation values in each direction, i.e. $\langle \hat{\mathbf{A}} \rangle = (\langle \hat A_x\rangle, \langle \hat A_{y}\rangle, \langle \hat A_{z}\rangle)^T$.

The idea of an expectation value is a very nuanced one, because the "average value" of a series of measurements has to be very precisely defined in the context of an expectation value. The expectation value is the averaged value you would get for some measurement of a system (position, momentum, energy, etc.) if you measure a billion identical copies of the same system or if you repeatedly reset the system to an identical initial state prior to each measurement. Quantum-mechanically, if we just make an arbitrary set of measurements without taking care to make sure the system starts off in the same original state, the measurements will themselves change the state of the system and spoil the average of any measurement!

Examples of abstract linear operators

The first example of a linear operator we will consider is called the projection operator $\hat P$. The projection operator is defined by:

$$ \hat P = |\alpha\rangle \langle \alpha| $$

If you have studied linear algebra, you may notice that this is very similar to the idea of a vector projection. Essentially, the projection operator tells us how much of one vector exists along a particular axis (although the axis is, again, in some direction in a complex Hilbert space, not real space). The component of a ket $|\psi\rangle$ in the direction of the basis vector $|\alpha\rangle$ is then given by $\hat P|\psi\rangle$. To demonstrate, let's consider a 3D ket $|\psi\rangle$ in a Hilbert space, which, in column vector form, is given by:

$$ |\psi\rangle = \begin{pmatrix} c_\alpha \\ c_\beta \\ c_\gamma \end{pmatrix} $$

Let us choose an orthonormal basis ${|\alpha\rangle, |\beta\rangle, |\gamma\rangle}$ in which we can write $|\psi\rangle$ in basis-vector form as:

$$ |\psi\rangle = c_\alpha|\alpha\rangle + c_\beta |\beta\rangle + c_\gamma|\gamma\rangle $$

Now, let us operate the projection operator on $|\psi\rangle$. This gives us:

$$ \begin{align*} \hat P |\psi\rangle &= |\alpha\rangle \langle \alpha|\psi\rangle \\ &= |\alpha\rangle \big[ c_\alpha \langle \alpha|\alpha\rangle + c_\beta\langle \alpha|\beta\rangle + c_\gamma \langle \alpha|\gamma\rangle\big]\\ &= |\alpha\rangle \big[ c_\alpha \underbrace{\langle \alpha|\alpha\rangle}_{1} + c_\beta\cancel{\langle \alpha|\beta\rangle}^0 + c_\gamma \cancel{\langle \alpha|\gamma\rangle}^0\big]\\ &= c_\alpha|\alpha\rangle \end{align*} $$

Note: The above derivation works because our basis is orthonormal, meaning that the basis vectors are normalized ($\langle \alpha| \alpha\rangle = \langle \beta| \beta \rangle = \langle \gamma|\gamma \rangle = 1$) and orthogonal ($\langle i|j\rangle = 0$, for instance $\alpha|\beta\rangle = 0$).

Another one of the essential properties that defines a projection operator is that $\hat P^2 = \hat P$, which is called idempotency. We can show this as follows:

$$ \begin{align*} \hat P^2|\psi\rangle &= \hat P(\hat P|\psi\rangle) \\ &= \hat P (c_\alpha|\alpha\rangle) \\ &= c_\alpha \underbrace{|\alpha\rangle \langle \alpha|}_{\hat P}\alpha\rangle \\ &= c_\alpha |\alpha\rangle \underbrace{\langle \alpha|\alpha\rangle}_1 \\ &= c_\alpha |\alpha\rangle \end{align*} $$

This only works if the projection operator is the outer product of the same state i.e. $|\alpha\rangle \langle \alpha|$ and that $|\alpha\rangle$ is a normalized vector. Indeed, $\hat A = |\psi\alpha \langle \beta |$ is not a valid projection operator, and neither is $\hat B = |\alpha\rangle \langle \alpha|)$ if $\langle a|a\rangle \neq 1$. Likewise, it is also only true if the projection operator is linear, which is what allowed us to say that $\hat P^2|\psi\rangle = (\hat P \hat P)|\psi\rangle = \hat P(\hat P |\psi\rangle)$.

The adjoint and Hermitian operators

Another important property of nearly all operators we consider in quantum mechanics is that they are Hermitian operators. What does that mean? Well, consider an arbitrary operator. The adjoint of an operator is defined as its transpose with all of its components complex-conjugated. We notate the adjoint of an operator $\hat A$ as $\hat A^\dagger$ and read it as "A-dagger" (this is for historical reasons as physicists wanted a symbol that wouldn't be confused with the complex conjugate symbol, not because physicists like to swordfight!). The idea of adjoints may sound quite abstract, so let's see an example for a 2D Hilbert space. Let us assume that we have some operator $\hat A$, whose matrix representation is as follows:

$$ \hat A = \begin{pmatrix} c_{11} & c_{12} \\ c_{21} & c_{22} \end{pmatrix} $$

Then, the adjoint $\hat A^\dagger$ of $\hat A$ is given by:

$$ \hat A^\dagger =\begin{pmatrix} c_{11}^* & c_{12}^* \\ c_{21}^* & c_{22}^* \end{pmatrix}^T = \begin{pmatrix} c_{11}^* & c_{21}^* \\ c_{12}^* & c_{22}^* \end{pmatrix} $$

For example, let's take the adjoint of a very famous matrix operator in quantum mechanics (the Pauli $y$-matrix):

$$ \begin{pmatrix} 0 & -i \\ i & 0 \end{pmatrix}^\dagger = \begin{pmatrix} 0& -i \\ i & 0 \end{pmatrix} $$

Notice here that to find the adjoint of $\hat A$ we complex-conjugated every component of the matrix, and then transposed the matrix. This procedure works for any operator when it is in matrix representation. This is a straightforward rule to remember - if we're given an operator in matrix form, complex-conjugation and transposing gives us the adjoint.

Unfortunately, if we consider an abstract operator (for instance, the projection operator) where we don't know its matrix form, there is usually no general formula that relates $\hat A$ and $\hat A^\dagger$. However, there are some special cases:

- A constant $c$ has adjoint $c^\dagger = c^*$

- A ket $|a\rangle$ has adjoint $|a\rangle^\dagger = \langle a|$

- A bra $\langle b|$ has adjoint $\langle b|^\dagger = |b\rangle$

- An operator $\hat A$ satisfying $\hat A|\alpha\rangle = |\beta\rangle$ has $\langle \alpha|\hat A^\dagger = \langle \beta|$

- An inner product $\langle a|b\rangle$ has adjoint $\langle a|b\rangle^\dagger = \langle b|a\rangle$

- An operator inner product $\langle a|\hat A|b\rangle$ has adjoint $\langle b|\hat A^\dagger|a\rangle^*$